Submitted by Kathelene McCarty Smith, Department Head, Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

A letter found in the papers of Dr. Charles Duncan McIver, the founder and first president of the State Normal and Industrial School (now The University of North Carolina at Greensboro), noted that he had always wanted to see a “first class [train] wreck.” He got his wish on the night of August 25, 1902, when Southern Railway’s Fast Mail Train No. 35 ran off the rails near Harkins, South Carolina. Fast Mail express trains had been operated by Southern Railway since the late 19th century and were particularly perilous because of their speed. But they were attractive to some passengers, such as Dr. McIver, as they often journeyed at night and were faster than the alternative methods of travel. He booked a seat on the No. 35 train in hopes of a quick trip to Atlanta, Georgia, to speak at the Teachers’ Institute.

.jpg)

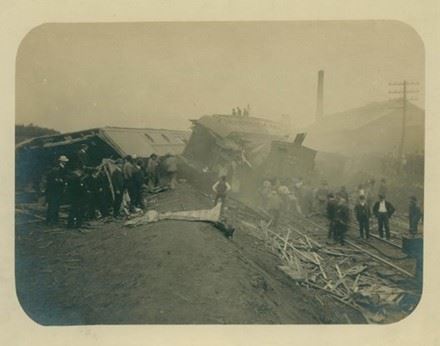

The train, which carried the mail from New York to Atlanta, was running at the rapid speed of sixty miles per hour when it encountered a sabotaged section of the track. The conductor, Henry Busha, who was injured in the wreck, blamed the incident on “miscreants” whose mischief caused the train to hit the open switch and careen off the tracks, leaving the engine, mail car, baggage car, and coaches stranded on their sides. Busha made it a point to tell reporters that he had not jumped out of the engine but crawled to safety; thus, keeping his pride intact and ensuring that he was not to blame. News accounts considered it “nothing short of a miracle” that no one was killed, although several people were seriously injured. Many witnesses who were at the scene saw nothing wrong with the switch and believed that there was no evidence of foul play, but railroad authorities believed that there was proof of premeditative tampering, as a crowbar was found, and spikes were pried out of a side track. Believing that the saboteurs might still be nearby, bloodhounds were employed in efforts to hunt them down, but to no avail.

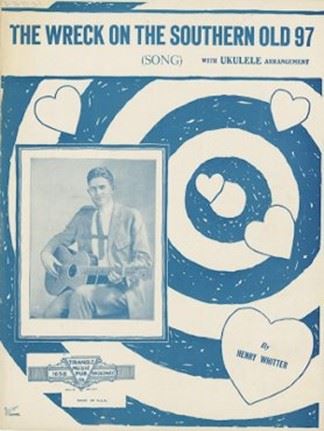

Train wrecks were not uncommon in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and some included Fast Mail trains like the one Dr. McIver rode. One of the most famous occurred almost a year after McIver’s experience. On September 27, 1903, another Southern Railway Fast Mail train jumped the track near Danville, Virginia. Like the event that took place the year before, this crash was partially caused by the accelerated speed of train in the attempt to make up for lost time. The momentum resulted in a plunge of forty-five feet off the Stillhouse Branch trestle. The wreck soon became a public spectacle, and many people came to view the horrible scene. Eleven members of the crew perished, and almost everyone on the train was injured, becoming the worst train wreck in the history of the state of Virginia. Soon lore began to supersede facts, and ghostly figures and train whistles began to be witnessed. The incident even inspired the 1924 hit country song “The Wreck on the Southern Old 97,” which sold six million records, and since has been recorded by many country artists.

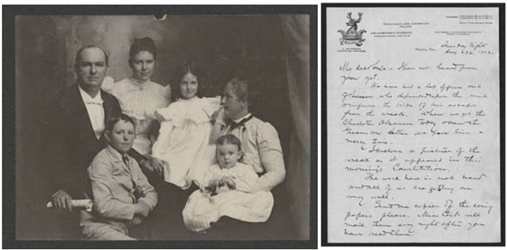

Dr. McIver knew that his wife, Lula, had been worried about his propensity for riding on night trains. In fact, she wrote her husband a letter only a few weeks before the wreck expressing her concerns. She cited a recent train wreck that occurred at night, and she expressed a strong preference for him to travel by day – even if it delayed his homecoming several hours. He noted her apprehension but countered with this comment made by Mark Twain: An insurance man tried to sell Twain a policy as he was boarding a train. Twain told him, “No, I don’t want it. More people die in beds than on trains.”

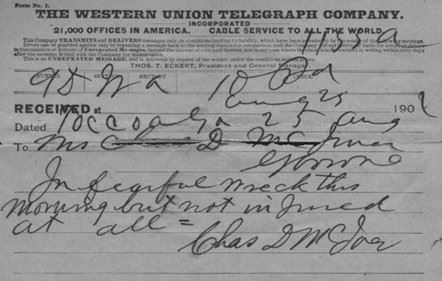

Mrs. McIver’s fears were realized when her husband’s train went off the rails in the early hours of August 25. She did not accompany her husband to Atlanta but remained at home on the college campus with their small family. As soon as he was able, he sent her a Western Union telegram reading, “In fearful wreck this evening but not injured at all.” After Dr. McIver was settled in his “delightful room on the fifth floor” of his Atlanta hotel, he wrote to Lula again, regaling her of his adventure. He described the general pandemonium after the wreck, especially the cries of “murder” from an older passenger. He wrote that the engine that “lay flat on the side and whistled mournfully for 20 minutes” and the wood which was strewn everywhere and eventually used for a bonfire. He even enclosed a piece of the wood in his letter as a “souvenir of the wreck.” His general tone was surprisingly cheerful, no doubt to soothe his wife’s panic, and he closed with “No news – Love to you all!

Ironically, Mark Twain’s story would not hold true for Dr. McIver. On September 17, 1906, he caught the early morning train to Raleigh, North Carolina, to meet a group who was traveling with politician William Jennings Bryan back to Greensboro. The train stopped in Durham for Bryan to make a campaign speech and for the party to have lunch. After lunch, McIver complained of indigestion and acute chest pains, and decided to return to the club car to rest. He died shortly afterwards, suffering a stroke while returning from Raleigh – on a train.

Sources:

- President Charles Duncan McIver Records, Correspondence of Dr. and Mrs. McIver, 1892-1902; Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

- “Bad Wreck Due to Miscreants,” The Atlanta Constitution 26 Aug 1902, p 7.

- “Wreck of the Old 97,” Encyclopedia Virginia, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/wreck-of-the-old-97/